When I was first trying to decide what to make as the first “feature”, I figured user management was a good place to start. With Angular and ExpressJS playing somewhat nicely together, the next step is to get some users up and running. This will require a client-side piece – providing user information, as well as a server-side piece – storing information securely, validating provided information, and managing sessions.

There are two ways we can approach this – ultimately we’ll need to do both, so I don’t think it really makes much difference. Either we do the back end first or we do the front end first. Both strategies will require mocking the other part. If we do the back end first then we’ll need to govern the interactions right off the bat with test infrastructure or manually posting data. If we do the back end first, the whole “authentication” and “validation” phase will just be a stub. Both create the possibility for a design which doesn’t complement the other, so I don’t think it really matters too much. I’ll start with the UI just because I’m antsy to get something to look at with this web app.

Starting point

Over in the Angular set up post we got this killer app up and running:

Goal

- Create a publicly accessible landing page, the default when visiting the app

- Create a “profile” page accessible only to logged in users accessible through some kind of navigation element

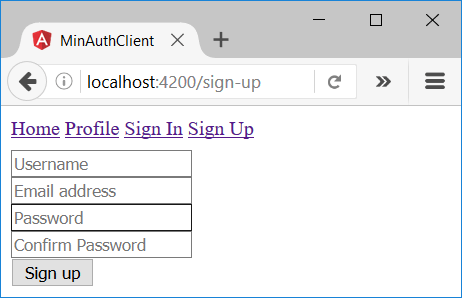

- Create a sign up page for new users – form with username and password and a “sign up” button

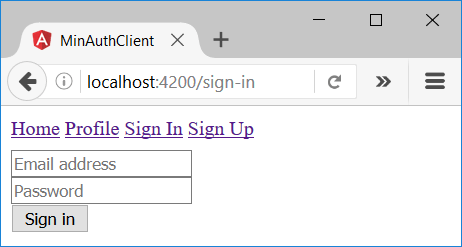

- Create a sign in page for existing users – form with username and password and sign out button

- Create persistent indication of whether the user is signed in or signed out

What this looks like at this stage is not really much of a consideration at this point, the important part right now is getting this all working.

Doing it

We’ll need at least 4 “pages”: landing, sign up, sign in, and a profile. Additionally, it’d be nice to have a static header for navigation as persistent place to put all this stuff. Let’s generate a bunch of placeholders quickly:

$ ng g c landing installing component create src\app\landing\landing.component.css create src\app\landing\landing.component.html create src\app\landing\landing.component.spec.ts create src\app\landing\landing.component.ts update src\app\app.module.ts $ ng g c sign-up installing component create src\app\sign-up\sign-up.component.css create src\app\sign-up\sign-up.component.html create src\app\sign-up\sign-up.component.spec.ts create src\app\sign-up\sign-up.component.ts update src\app\app.module.ts $ ng g c sign-in installing component create src\app\sign-in\sign-in.component.css create src\app\sign-in\sign-in.component.html create src\app\sign-in\sign-in.component.spec.ts create src\app\sign-in\sign-in.component.ts update src\app\app.module.ts $ ng g c profile installing component create src\app\profile\profile.component.css create src\app\profile\profile.component.html create src\app\profile\profile.component.spec.ts create src\app\profile\profile.component.ts update src\app\app.module.ts $ ng g c header installing component create src\app\header\header.component.css create src\app\header\header.component.html create src\app\header\header.component.spec.ts create src\app\header\header.component.ts update src\app\app.module.ts

Let’s get the basic routing out of the way to start – add the header as a persistent element right to the root element.

// app.component.ts + import { HeaderComponent } from './header/header.component'; @Component({ selector: 'app-root', template: ` +

Strip the root element of anything other than the header and the router outlet:

// app.component.ts ... - <h1> - {{title}} - </h1> <router-outlet></router-outlet> `, styles: [] }) - export class AppComponent { - title = 'app works!'; - } + export class AppComponent {}

Replace what was previously the app root with the landing page:

// app-routing.module.ts ... + import { LandingComponent } from './landing/landing.component'; const routes: Routes = [ - { - path: '', - children: [] - } + { path: '', component: LandingComponent } ]; ...

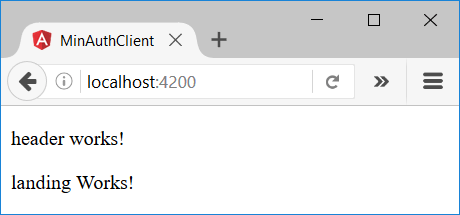

Now we have this beautiful evolution of the previous page (ooooh, ahhhhh):

Lets set up the navigation for the rest of the “pages”. To do so, we’ll use the header for everything just because it’s a relatively conventional thing and it’s easy at this point. For the first pass we’ll do the bare minimum:

// app-routing.module.ts ... + import { LandingComponent } from './landing/landing.component'; + import { ProfileComponent } from './profile/profile.component'; + import { SignInComponent } from './sign-in/sign-in.component'; + import { SignUpComponent } from './sign-up/sign-up.component'; const routes: Routes = [ - { - path: '', - children: [] - } + { path: '', component: LandingComponent }, + { path: 'sign-in', component: SignInComponent }, + { path: 'sign-up', component: SignUpComponent }, + { path: 'profile', component: ProfileComponent } ...

This gets us the very basic routing to let us see each of the new pages (at this point you can type the addresses into the browser and you should be able to see all your mundane “{component} works!” messages. Lets make this slightly more user friendly!

// header.component.html - <p> - header works! - </p> + <nav> + <a [routerLink]="['/']">Home</a> + <a [routerLink]="['/profile']">Profile</a> + <a [routerLink]="['/sign-in']">Sign In</a> + <a [routerLink]="['/sign-up']">Sign Up</a> + </nav>

That gets us a “navigation bar” with a wealth of opportunities for improvement, but should be enough to prove out the concept.

Sign up and sign in HTML

Putting the whole issue of looking good aside, as that’s a whole world of its own, we can toss in a quick minimalist UI signing up and signing in.

// sign-in.component.html - <p> - sign-in works! - </p> + <form> + <input type="text" placeholder="Email address"><br> + <input type="password" placeholder="Password"><br> + <button type="submit">Sign In</button><br> + </form>

// sign-up.component.html - <p> - sign-up works! - </p> + <form> + <input type="text" placeholder="Username"><br> + <input type="text" placeholder="Email address"><br> + <input type="password" placeholder="Password"><br> + <input type="password" placeholder="Confirm Password"><br> + <button type="submit">Sign Up</button><br> + </form>

No one will accuse this of being nice looking, but it should at least do the job for now. Note that these do a whole lot of nothing as it stands, they’re just raw HTML.

Angular-ize the forms

In the interest of making the forms actually useful, we’ll have to turn the raw HTML into something Angular can use. The Angular documentation is decent, so the only kind of tricky thing is the “confirm password” validation. Luckily the documentation for that is pretty good too! First things first, we’ll swap out the FormsModule for the ReactiveFormsModule – this means we’re going to put all the logic in the TypeScript file (the component) instead of in the HTML file. This makes the code actually unit testable, and generally scales better. People who are a fan of unobtrusive JavaScript are likely to see some familiar concepts – although to be fair the HTML is marked up with JavaScript in some places, so purists be warned.

// app.module.ts ... - import { FormsModule } from '@angular/forms'; + import { ReactiveFormsModule } from '@angular/forms'; ... imports: [ BrowserModule, - FormsModule, + ReactiveFormsModule, ...

Next comes the big chunk – sewing together the HTML and the Angular code to manage it. The sign-in functionality is marginally simpler, so that’s a good place to start. Here’s what we need to do from the HTML side of things:

- Bind the HTML form to a FormGroup object

- Set all the form control names to map inputs to their corresponding validations

- Capture the submit event

- Disable the

Sign Inbutton when the form is invalid (fields aren’t filled out)

It’s all relatively straightforward, but it’s good to review the documentation if its new.

// sign-in.component.html - <form> - <input type="text" placeholder="Email address"><br> - <input type="password" placeholder="Password"><br> - <button type="submit">Sign In</button><br> + <form [formGroup]="form" (ngSubmit)="onSignIn()"> + <input type="text" placeholder="Email address" formControlName="email"><br> + <input type="password" placeholder="Password" formControlName="password"><br> + <button type="submit" [disabled]="!form.valid">Sign In</button><br> </form>

From the component side of things, we need to wire everything up!

- Get rid of the unused

OnInit - Create a

FormGroupto associate with the HTML form - Build the desired validations for the elements

- Provide an

onSignUp()method to invoke when the form is submitted (we’ll just log the form for now)

// sign-in.component.ts - import { Component, OnInit } from '@angular/core'; + import { FormBuilder, Validators, FormGroup } from '@angular/forms'; + import { Component } from '@angular/core'; @Component({ selector: 'app-sign-in', templateUrl: './sign-in.component.html', styleUrls: ['./sign-in.component.css'] }) - export class SignInComponent implements OnInit { + export class SignInComponent { - constructor() { } + private form: FormGroup; - ngOnInit() { + constructor(private formBuilder: FormBuilder) { + this.form = formBuilder.group({ + "email": ["", Validators.required], + "password": ["", Validators.required] + }); + } + onSignIn(email, password) { + console.log(this.form); + } }

And that’s it for the easy one! Our form looks almost identical, but the submit button is disabled by default. On to the Sign Up form. The only real difference here is there’s an inter-field validation that happens between the two passwords – that can be tackled by nesting both inputs in a div. Other than that, everything is the same. It would be nice to put up an error message for when validations failed, but making this look nice and user friendly is a distant second priority to just pushing on ahead.

// sign-up.component.html - <form> - <input type="text" placeholder="Username"><br> - <input type="text" placeholder="Email address"><br> - <input type="password" placeholder="Password"><br> - <input type="password" placeholder="Confirm Password"><br> - <button type="submit">Sign Up</button><br> + <form [formGroup]="form" (ngSubmit)="onSignUp()"> + <input type="text" placeholder="Username" formControlName="username"><br> + <input type="text" placeholder="Email address" formControlName="email"><br> +

+ + +

+ <button type="submit" [disabled]="!form.valid">Sign Up</button><br>

</form>

And the component, with its password checking validator:

// sign-up.component.ts - import { Component, OnInit } from '@angular/core'; + import { Component } from '@angular/core'; + import { FormBuilder, FormGroup, Validators } from '@angular/forms'; @Component({ selector: 'app-sign-up', templateUrl: './sign-up.component.html', styleUrls: ['./sign-up.component.css'] }) - export class SignUpComponent implements OnInit { + export class SignUpComponent { - constructor() { } + private form: FormGroup; - ngOnInit() { + constructor(private formBuilder: FormBuilder) { + this.form = formBuilder.group({ + "username": ["", Validators.required], + "email": ["", Validators.required], + "passwords": formBuilder.group({ + password: ["", Validators.required], + repeatPassword: ["", Validators.required] + }, { validator: this.passwordMatchValidator }) + }); + } + onSignUp() { + console.log(this.form); + } + passwordMatchValidator(group: FormGroup) { + return group.get('password').value === group.get('repeatPassword').value + ? null : { 'mismatch': true }; + } }

And once again, our form looks identical other than the disabled button by default. Now we have forms that still don’t work, but are marginally closer to working. Progress!