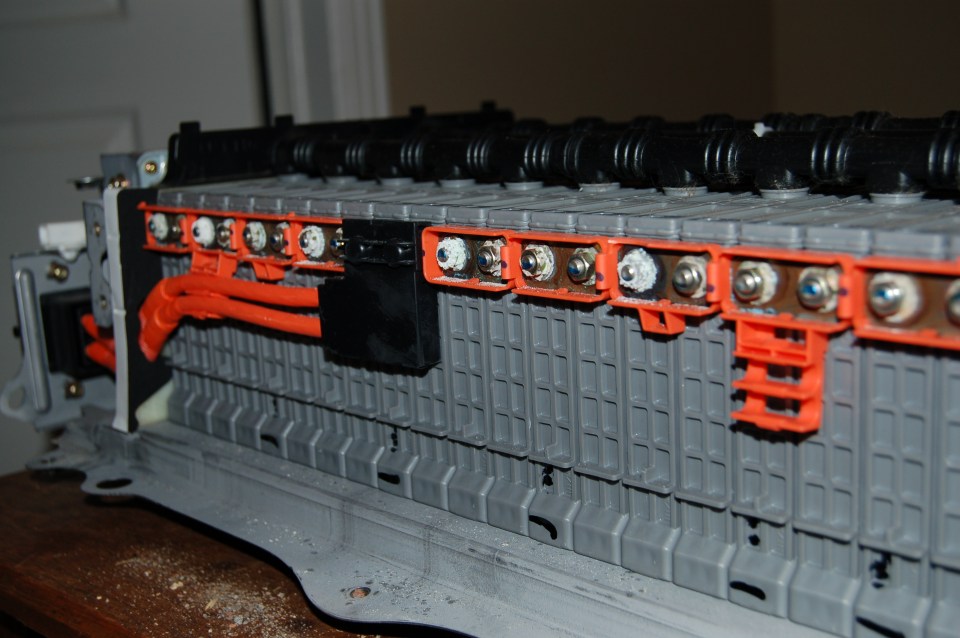

The charge/discharge cycling of the modules is remarkably uneventful. Attach leads to module bolts, fasten nut on to keep it in place, press start on the charger, wait a day and a half. Repeat, repeat, repeat…

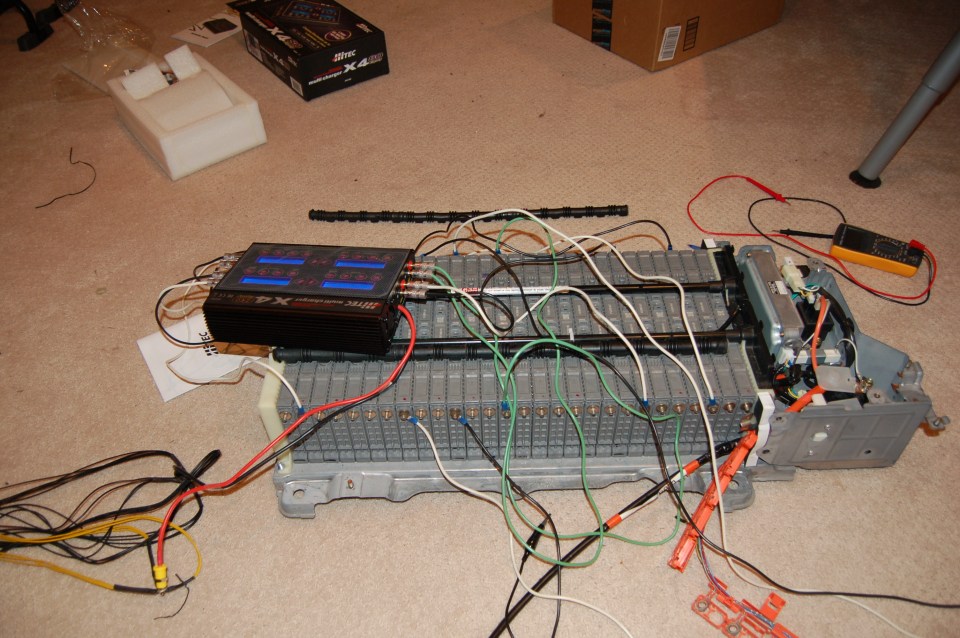

More than a little bit messy…

I tried to spread out the modules I was charging at any given time, so as to not accidentally overheat any. This ended up not being much of a concern, as almost immediately all the charge cycles became out of sync and offset themselves anyways. Having to keep an eye on all 8 was a bit of a pain – they would sometimes finish hours apart from one another.

I copied down the discharge from each of the cycles of each of the modules. Note that these follow the settings in the previous blog post (7250 mAh charge, discharge to 6V)

| Module | Discharge 1 | Discharge 2 | Discharge 3 |

| 1 | 4288 | 5730 | 5874 |

| 2 | 4012 | 5608 | 5798 |

| 3 | 4067 | 5555 | 5691 |

| 4 | 4315 | 5669 | 5776 |

| 5 | 3504 | 5297 | 5583 |

| 6 | 4270 | 5730 | 5804 |

| 7 | 4414 | 5777 | 5916 |

| 8 | 4384 | 5691 | 5814 |

| 9 | 4237 | 5627 | 5697 |

| 10 | 4350 | 5659 | 5786 |

| 11 | 3256 | 5180 | 5487 |

| 12 | 3625 | 5428 | 5609 |

| 13 | 1444 | 1786 | 1811 |

| 14 | 3810 | 5571 | 5825 |

| 15 | 2346 | 4615 | 5375 |

| 16 | 3394 | 5064 | 5579 |

| 17 | 4318 | 5748 | 5885 |

| 18 | 3518 | 5475 | 5761 |

| 19 | 2190 | 5884 | 5871 |

| 20 | 4315 | 5526 | 5746 |

| 21 | 4396 | 5732 | 5858 |

| 22 | 4299 | 5635 | 5776 |

| 23 | 4372 | 5665 | 5796 |

| 24 | 4358 | 5635 | 5745 |

| 25 | 4417 | 5653 | 5758 |

| 26 | 4494 | 5668 | 5782 |

| 27 | 4095 | 5569 | 5741 |

| 28 | 4528 | 5504 | 5687 |

| New module 1 | 3603 | 5319 | 5589 |

| New module 2 | 4922 | 6067 | 6086 |

As you can see, it’s quite obvious that module 13 doesn’t have anywhere near the capacity of any of the other modules. This is consistent with my initial voltage check. Also, I botched the first cycle of module 15 and 19. Module 15 was still looking to be a little on the low end of the spectrum so I repeated the discharge cycle and obtained a measurement of 5579 mAh, which is much more consistent with the other modules.

As a side note, looking solely at this metric as an indicator of health, one of the new modules was the “healthiest” module I had, while the other one was almost at the bottom of the pack (but not quite). From that perspective, I’m thrilled with my purchase – it would have sucked to have gotten to this stage and only then figured out a module was garbage. Note that this doesn’t necessarily mean either of the modules is an ideal fit for my battery pack, but making that determination is beyond the means of my equipment and knowledge. My hope is that the only manifestation of the differing capacities in modules will be disproportionate wear on the “healthy” module until it’s more in line with the others.